Varsha rtu seduces, surprises, and satiates us in ways that artists have tried to articulate and capture for over two millennia. But perhaps the most evocative expression of Monsoon is found in music. The season of rain permeates both the classical and folk traditions of music in the subcontinent

Amrit Mohan

The Indian Monsoon is unique. It can be intense. It can be dramatic. And no matter how eagerly you await its arrival through the heat of summer, it always catches you off guard with its sheer majesty and wild spirit. It fills your heart with a euphoria that only a force of nature can instil. It seduces, surprises, and satiates in ways that people have tried to articulate and capture for centuries. In fact, the word Monsoon was first used to describe this very phenomenon – the subcontinent’s season of rains.

It is then no surprise that this beautiful, unbridled season moves the romantics among us – the poets and the artists – the most. The inspiration offered by this season seems boundless judging by the sheer volume of Monsoon related art. Painting, literature, music, poetry, songs… the season of rains inspires artists and works across forms in the subcontinent.

In literature we can go from Kalidasa’s two-thousand-year-old masterpiece Meghdutam to Rabindranath Tagore’s 20th century ode to this season, Abar Esheche Ashar (The Monsoon Has Come Again).

Travellers to the subcontinent, from antiquity to the modern day too have documented this remarkable Indian season.

These include works like the Iranian traveller Al-Biruni’s account - Tahqiq-i-Hind in the 11th century and 19th century British scholar James Tod’s Travels in Western India. British-Australian travel writer Alexander Frater’s account of the Indian Monsoon, Chasing the Monsoon: A Modern Pilgrimage through India, published in 1990, is considered a modern classic.

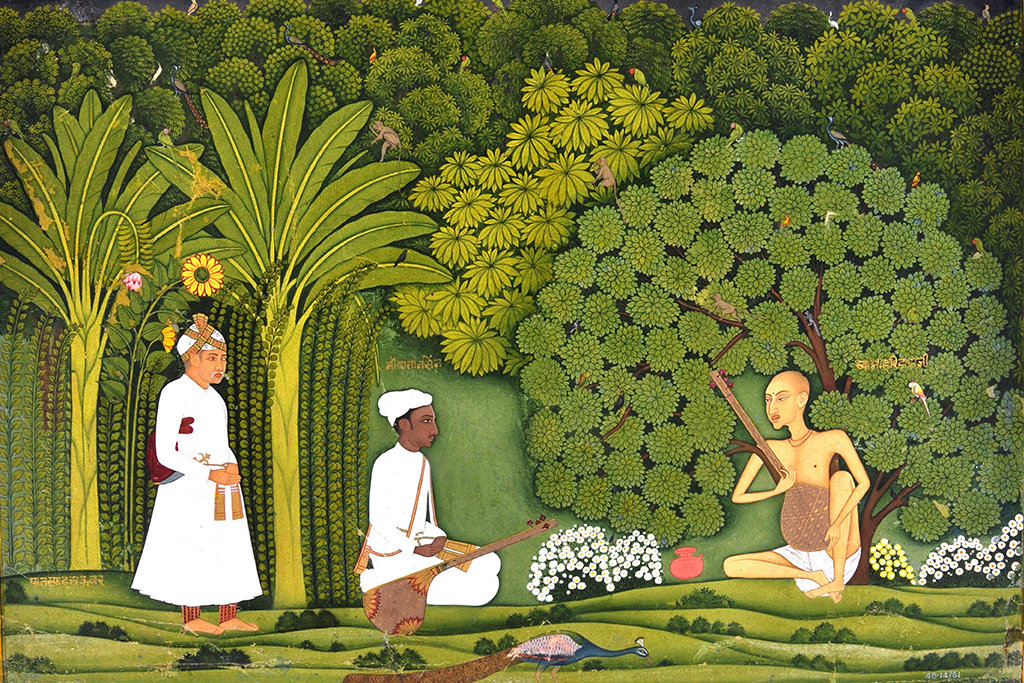

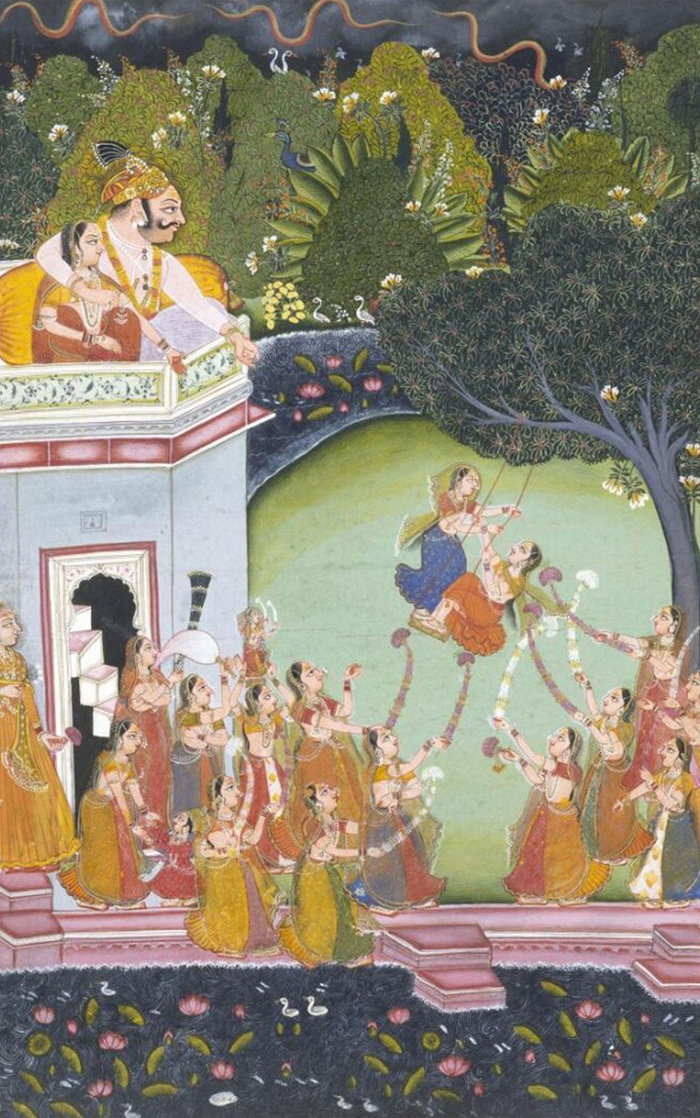

Possibly the most evocative visual expressions of Monsoon lies in the Ragamala (“Garland of Ragas”) paintings from the 16th century. These are a suite of miniature paintings in which art, poetry and classical music are amalgamated seamlessly. The season of rains continues to be a muse for modern artists, as seen in M. F. Husain’s Portrait of an Umbrella series and Sanjay Bhattacharya’s Rainy Day, Kolkata.

But perhaps it is in music that Monsoon finds its richest expression. It saturates with its magic both, the classical and the traditional folk music of the subcontinent.

Traditional and Folk Music

Folk music is the music of the people. It is deeply informed by the culture, landscape and day to day experience of a community. It is also a ritual of social celebration, one in which the entire community participates. One of the key elements of folk music is the simplicity of the melody, lyrics and rhyme scheme. Another is its ability to foreground a lived experience.

Every region has its own folk music specific to the Monsoon season. Some describe the life-giving role that this season plays while others celebrate the respite it brings from the months of hot summer that precede it.

Untitled, c. 1770. The celebration of Teej. V&A Museum

In Punjab

the Monsoon

is embraced with

the festival of

Teeyan (Teej)

and the traditional

folk music includes

many songs

dedicated to

the rains.

Most of

these songs

are composed

and sung

by women.

Maharashtra: Traditional Bhilari and Shetkari songs are sung to welcome the rains in Maharashtra. These are songs about the sowing of crops, which has to be done just before the rains arrive. As the farmers sow they sing these songs to invoke a season of bountiful rains to help the crops grow.

Uttar Pradesh: Kajri is a tradition of folk music from UP that celebrates the Monsoon. Some of the songs from this tradition have become so popular over time that the original Bhojpuri songs have seen several reinterpretations in Awadhi and Maithili languages and in the subgenre of Thumri (the local styles of neighbouring regions).

Manipur: Amongst the Meitei people of Manipur one of the most popular folk songs is Kumdam Eshei. It is inspired by a beautiful fable. There were once six maidens who fell in love with six young men. However, these men were not considered suitable matches by the maidens’ families. Unwilling to part the young lovers decided to fly up into the sky and live there. As they made their way, one of the maidens birthed a child – a cicada. Telling her son that he could not accompany her into the sky, she made him the promise that once every year she would watch him from up there, and that it would be his responsibility to announce the arrival of Monsoon to the people on earth. “O Cicada! Tell us the Monsoon has arrived”, proclaims a line from the song.

Himachal Pradesh: Each of Himachal Pradesh’s 12 districts has its own traditional folk songs about the Monsoon, which celebrate the rains and also beautifully reflect the differences in the topography of the region. Because the experience of the rains is also impacted by that topography.

Punjab: In Punjab the Monsoon rains are embraced with the festival of Teeyan (Teej) and the traditional folk music includes many songs dedicated to the rains. Interestingly most of these songs are composed and sung by women.

Rajasthan: The Manganiar community of Rajasthan also boasts a rich repertoire of Monsoon music. The traditional minstrel community of the desert state, in days past they were asked by Rajput rulers to sing and pray for rain in local temples. Even today, the relationship between the region’s music and Monsoon is considered sacred. “The lyrics of the rain songs in Rajasthan reflect hope, love and longing”, says the renowned folk and Sufi singer Mame Khan.

Indian Classical Music

Indian classical music is the world of ragas. Ragas are designed to evoke particular emotions and are therefore rendered at particular times – of the day, and of the season. Bharata’s Natya Shastra, a two-thousand year-old treatise on performing arts, lists around 30 ragas – making the ragas one of the oldest classical forms of music in the world. Today, there exist hundreds of variations, a beautiful testament to the ever-evolving nature of this art-form.

Raga Malhar: The word Malhar is derived from the Sanskrit words ‘mala’ and ‘hari’. Literally translated, it means “uncleanliness remover”. Being the raga associated with torrential rains, the arrival of Monsoon after the hot summer has inspired numerous variations of Raga Malhar. Prominent folk musician Kutle Khan says that most gharanas (communities of performers who share a distinctive musical style traced to a particular instructor or region) compose in Raga Malhar in their own distinct styles, coming up with many variations.

Mian ki Malhar: One such variation is Raga Mian ki Malhar, attributed to Tansen, the famed maestro in Emperor Akbar’s court. Interestingly, the popularity of this variation has gone on to exceed that of the original, so much so that if “Malhar” is mentioned today, it most likely refers to Mian ki Malhar.

Raga Megh: One of the oldest ragas, Raga Megh gets its name from the word ‘megh’, which literally means cloud. An exquisite raga, it was traditionally believed to hold the power to invoke rain. Also a raga of anticipation, it beautifully expresses the longing and anticipation one feels for the rains as the summer draws to a slow end.

Raga Megh Malhar: A fusion of two traditional rain ragas, Megh and Malhar, Raga Megh Malhar is considered extremely powerful and evocative. Legend has it that jealous courtiers once asked Emperor Akbar to test Tansen’s musical abilities by making him sing Raga Deepak. When performed properly, Raga Deepak was believed to make the air so hot the performer would burn to ashes. The courtiers were certain that performing Raga Deepak would lead to Tansen’s death. And sure enough, being the superlative singer that he was, he performed it so well that all the lamps of the court lit up, and his body came close to perishing. What the courtiers didn’t know was that for the two weeks before the performance, Tansen had taught his daughter Saraswati, an accomplished musician in her own right, and her friend Rupvati to sing Raga Megh Malhar to perfection. He had instructed them to start singing only when the lamps started burning. As the air became steadily hotter during his performance, drying the leaves off trees and boiling the water in the rivers, flames shot up out of nowhere, lighting up the lamps in court. Just then, Saraswati and Rupvati began singing Raga Megh Malhar, summoning forth rain clouds which drenched the land in a cooling shower of rain, saving Tansen’s body from succumbing to the heat generated by his spectacular performance.

The majesty and force of the Monsoon, the magic of the rains, and the power this season holds over the romantics and the hopefuls, the lovers and the writers, the painters and the musicians, continues to inspire their work even today.

Explore the magic of Monsoon music in the classical and popular traditions with Paro’s specially curated playlists: