Basant rtu - that most whimsical and unpredictable time of year - has inspired many an ode over thousands of years. It finds rich and beautiful expression in one of the oldest forms of classical music in the world - the Indian classical tradition

With its blue skies, blooming flowers, rivers replenished from freshly melted snow, and signs of new life flourishing all around, is it any wonder that there exist countless odes to Basant rtu in the subcontinent? It is the most whimsical and unpredictable time of year. It is strange and yet joyous. All kinds of weather come together in Basant – the day can feel hot, the night can be chilly, and every now and then the sky teases a downpour. But in the midst of this frenzy there is also the hope of a new beginning – the annual cycle of seasons, Rtu Chakra, starts afresh. And the change that Basant ushers in permeates our entire world. It changes the very quality of the light and the air. The pallid rays of the winter sun give way to brighter, warmer sunlight that nurtures new life.

The beauty of Basant rtu has inspired many an ode for thousands of years. Rabindranath Tagore wrote, “Spring is the time for the woodlands to flower; it is the time for life to overflow and a time for festal blooming. The trees and plants become mad to give themselves away; they become prodigal… Are we in no way related to those plants and trees which are in flowers invigorated by the secret elixir of spring? They are covering our courtyard under their shades; filling it with fragrance they are surrounding us in an embrace…”

This sense of hope is captured beautifully not only in literature, but in the music of the subcontinent as well.

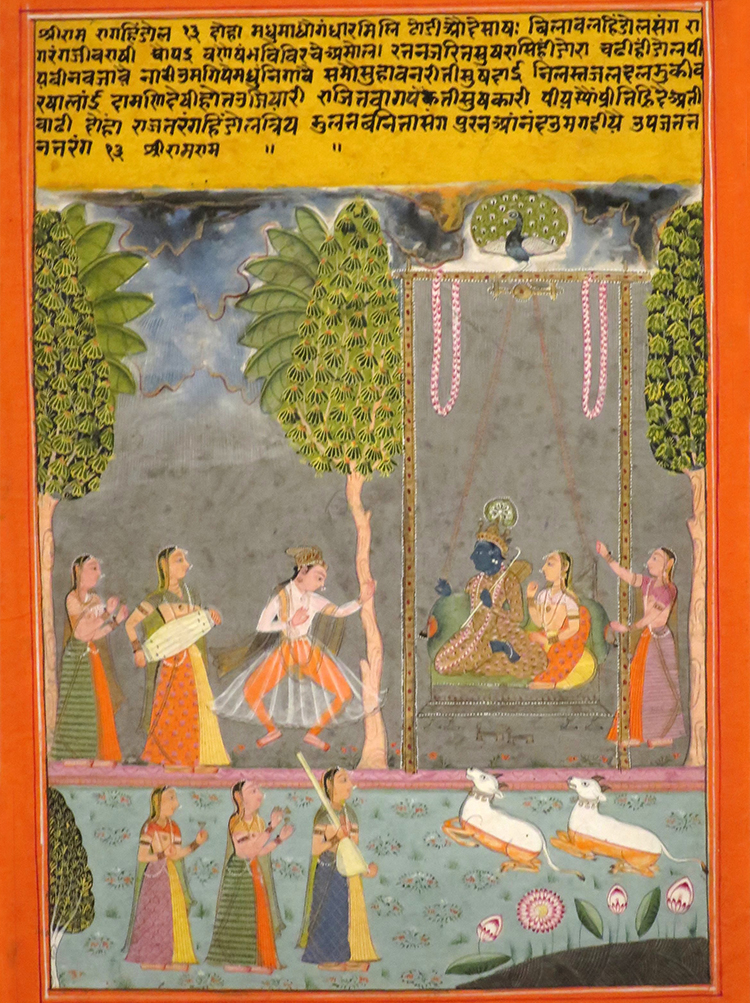

The season of Basant finds very distinctive representations in Indian classical music. The subcontinent is home to one of the oldest forms of classical music in the world. And the raga is the foundation on which this rich and ancient tradition has been built. Ragas are unique. There is no comparable equivalent for them in Western classical music. A raga is not a tune – an infinite number of tunes can be based on the same raga. It is not a scale – many ragas can be based on the same scale. According to Brihaddeshi, an ancient Sanskrit text on Indian classical music, a raga is “a combination of tones which, with beautiful illuminating graces, pleases the people in general”. It can be challenging to put this fascinating notion into a short, simple definition. It may roughly be understood as a concept that resides somewhere between tune and scale. And this beautiful language of music is made even richer by the long, unbroken tradition of actively encouraging improvisation. In fact, improvisation is a key element of Indian classical music. The goal is to create a rasa – a mood, an atmosphere, a feeling in the depths of our being – and using the basic melodic framework of a raga, an artist is free to add individual expressions into a composition to create this rasa.

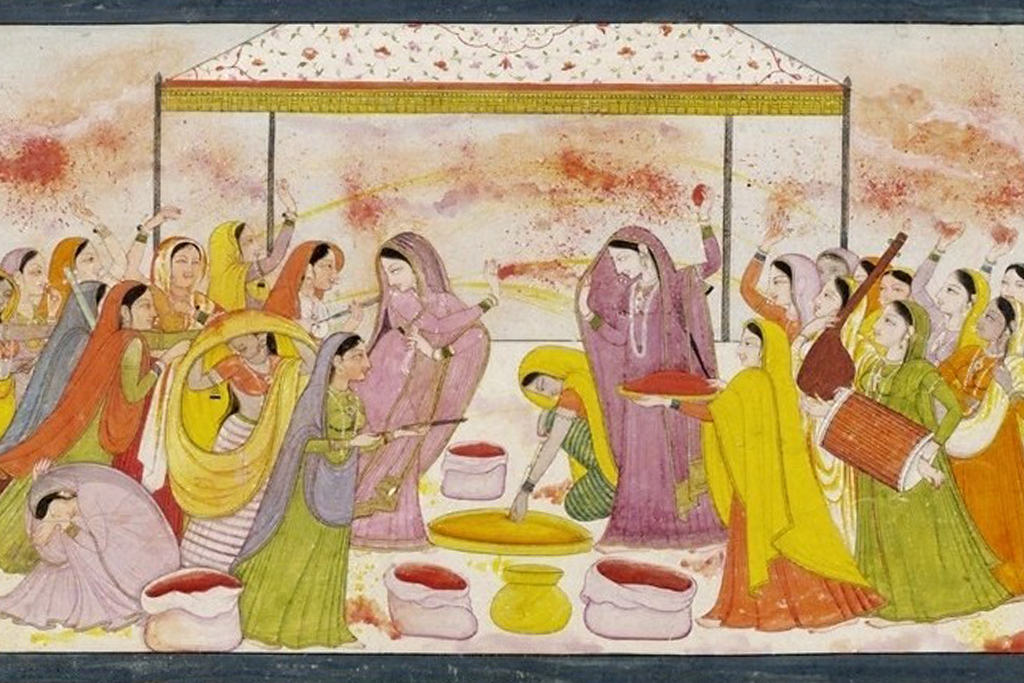

Raga Hindol

has often been

associated with Spring.

It is considered a manifestation

of Kama,

the god of love.

It is also linked

to the

festival of

‘dola’ - the spring

festival of

colours better

known as Holi

Ragas themselves have long been associated with the natural world and its elements. In fact, in the traditions of the subcontinent, ragas are believed to naturally exist – an artist doesn’t invent them, they merely discover them. In the Hindustani classical tradition, ragas are very often aligned with specific times of day and seasons. Because ragas can help our body and mind process the rhythms of nature, and the changes that they bring. There are hundreds of ragas mentioned across many ancient texts, and each shares a close association – with a specific time, a deity, an occasion, an energy. The three ragas that sing of Basant are Raga Hindol, Raga Basant, and Raga Bahar.

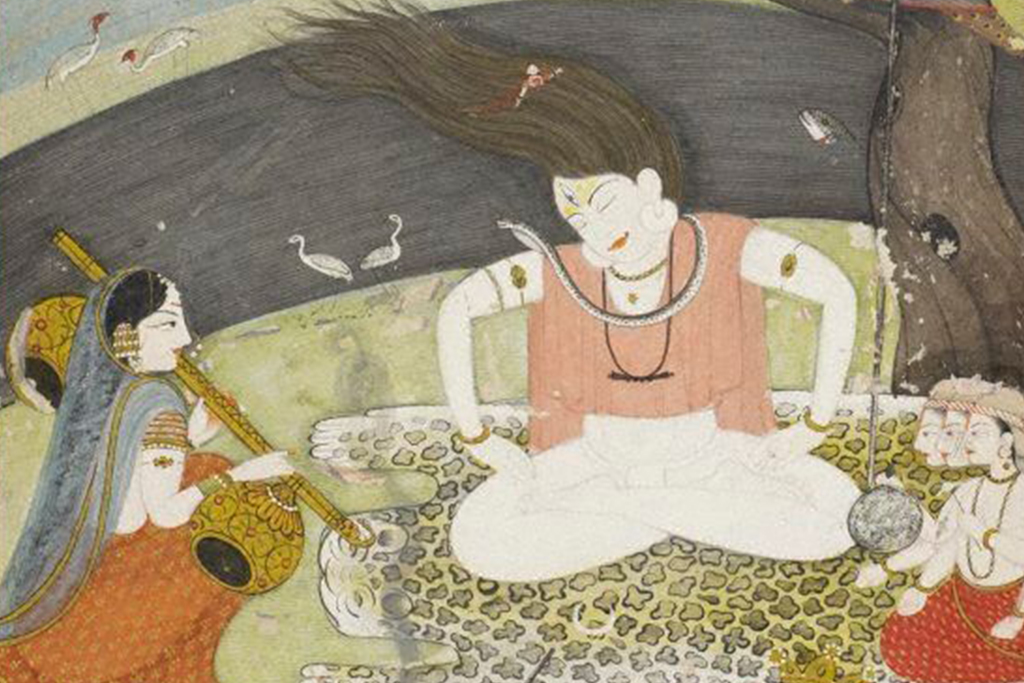

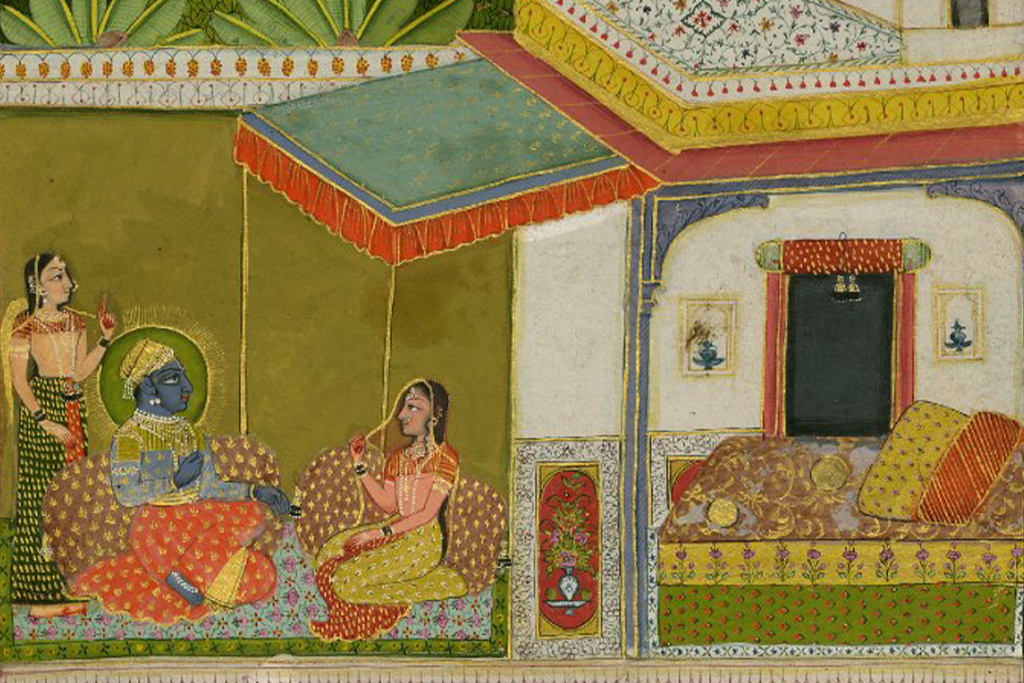

Raga Hindol has often been associated with Spring. It is considered a manifestation of Kama, the god of love. It is also linked to the festival of ‘dola’ – the spring festival of colours better known as Holi. Nanyadeva, the 11th century ruler and author of the musicological treatise Sarasvati Hridayalankara, recommends Raga Hindol as the ideal raga for spring. It is recommended that this raga be performed during the first half of the day. A beautiful raga, it gently lulls you into the serenity of the composition. Soon you find yourself celebrating the sweet smell of spring and the joy of life and living that it brings. Ustad Rashid Khan’s 2001 rendition of Raga Hindol illustrates this in wondrous detail. His brilliant vocal performance is accompanied by Omkar Gulwadi on Tabla and Vishwanath Kanhere on Harmonium.

Most ragas are composed of seven notes. The tumultuous energy of Basant, the flurry of movement that characterises Spring in the subcontinent cannot be contained in seven notes. And so it is not surprising that Raga Basant is the only raga that uses all 12 notes of the scale. The smooth, elongated notes of this raga symbolise the magnificence, drama, and whimsical nature of Basant. An ancient raga that beautifully gives voice to the joy of spring, it sings of that southern breeze that Kalidasa said would announce the arrival of spring. Which is probably why several Sikh gurus have composed shabads (prayers) about the bounty of spring in Raga Basant. Mentioned as far back as the 8th century, for hundreds of years it has inspired songs of spring through the ever-evolving Hindustani classical tradition. In the 1970s-80s, numerous Tamil film soundtracks were composed in Raga Basant. And it continues to inspire classical musicians even today. A particularly beautiful rendition of this ancient raga was performed by the extraordinary Hindustani Classical violinist Kala Ramnath in 2016, accompanied by Pt. Yogesh Samsi on Tabla.

Bahar is the Persian word for spring. Centuries ago, the magic of Basant rtu moved yet another musician to write his own ode to the season. Amir Khusrau, the renowned 14th century Sufi musician is believed to have composed the beautiful Raga Bahar. It shares some similarities with Raga Malhar, but it has a unique quality to it – the characteristic twists in its notes perfectly articulate the unpredictable whimsy of Basant. Which probably also explains why during spring, this raga can be played at any time of the day. However, according to tradition, during the rest of the year Raga Bahar should only be performed in the early hours of the night. It is also considered one of the more challenging ragas to perform. Sarod maestro Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s spectacular 2016 performance of Raga Bahar is almost hypnotic. Accompanied by Sandeep Das on Tabla, it beautifully personifies that final tense moment which stretches and seems to last forever before spring finally arrives in all its splendour.

One of the many fascinating concepts in the world of Indian classical music is the jod-raga. The word ‘jod’ can literally be translated as ‘joint’, or ‘to join’. A jod-raga, when rendered well, is a beautiful amalgamation of two ragas that paints a single picture with indistinguishable parts. Two ragas come together, fusing to create a new entity altogether. Some, like Raga Basant-Bahar, seem to possess inherently complementary qualities. Not surprising, given that Basant and Bahar are Sanskrit and Persian for the same phenomenon – spring. Pratima Tilak’s 2018 performance of Raga Basant-Bahar is a breathtaking example of how entrancing a jod-raga can be. Accompanied by Pt. Omkar Gulvady on Tabla and Makarand Kundale on harmonium, the spectacular performance also features Tanpura and vocal support by Maneesha Kulkarni and Prajakta Kakatkar.

Perhaps the reason that Indian Classical Music is able to give voice to all the profound emotions that the seasons inspire in us is that it has never stopped evolving. For most of its history, Indian music has been an oral tradition. Unlike the western classical system of staff notations, there has been no written language for the musical traditions of the subcontinent. But as it has evolved through thousands of years, so it continues to evolve now. Over the last two centuries, a number of systems of writing sheet music for Hindustani Classical have been developed. The most prominent of these is the Bhatkhande Swar leepi (musical notations) developed by Pt. Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande in the early 20th century. An incredibly influential musicologist, Pt. Bhatkhande also created the thaat system of classifying ragas. For centuries, ragas were classified into raga (male), ragini (female), and putra (children). Pt. Bhatkhande’s system arranged all ragas across ten thaats (similar to but not the same as the western musical scale). Over the last century, the thaat system has become the prevalent system in use. Today, Pt. Bhatkhande’s works are considered to be an indispensable starting point for anyone looking to study Hindustani classical music. With the advent of the digital age, the Bhatkhande Swar leepi has already been taken a step further and adapted for computer use.

And so the jubilant arrival of spring continues to inspire new songs and ways to keep singing them. If we listen a little closer, we too can feel closer to the sun, the wind, the clouds, the birds, the trees as the poets and the painters, the singers and the musicians do. And that perhaps is what will allow us to truly hear the music of Spring.

Explore the many moods of Basant in classical and contemporary music with Paro’s specially curated playlist:

“Basant with Paro”– iTunes, Spotify

Cover Image: Radha Celebrating Holi, Unknown, 1788, V&A Museum

Wonderful and truly inspiring